Reconstructing the Past

- David

- Jan 25

- 3 min read

Updated: Jan 29

The so-called Nymphaeum generally attributed to Bramante outside the small southeastern Lazio town of Genazzano is familiar to any lover of Renaissance architecture. Christoph L. Frommel first gave it serious scholarly attention in an article from 1969, and it shows up since then in most survey histories of Italian Renaissance architecture. The building is a ruin, but almost surely not intended as one; instead, it’s an incomplete, rustic realization of an elegant idea.

Frommel proposed a schematic reconstruction, heavily influenced by the similarities he saw to Raphael’s Loggia of the Villa Madama. Recent digital reconstructions have taken the same tack, but with more (if not correct) classical detail (see here and here). I visited the ruin in the Spring of 2024, ostensibly to do some plein air painting and drawing of the picturesque subject. But it soon got me thinking about what a more convincing reconstruction might look like. I began developing one based on a digital survey provided for a competition for the site a few years earlier (that I did not in the end enter). The results of that reconstruction have been published in the recent 70th edition of the Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome (Open Access on jstor, and from academia.edu).

I’ll get to the process of writing a peer-reviewed scholarly article by someone who is not technically a scholar. But I first want to make the point that much of what I had to do to reconstruct the building involved imagination, since there is essentially no archival documentation that tells us what the architect (Bramante? Peruzzi?) intended. I would make the analogy to Early Music performers who try to reconstruct not only the score of Renaissance or Early Baroque music, but music practice of the time, in order to arrive as closely as possible at how the music actually sounded in its day. In the end, we can never know. But the reconstruction is most credible when it is performers doing the reconstruction—performers who are also scholars, or scholarly, but who must actually make the music in some particular way, and rely on their judgment as to what “sounds right.”

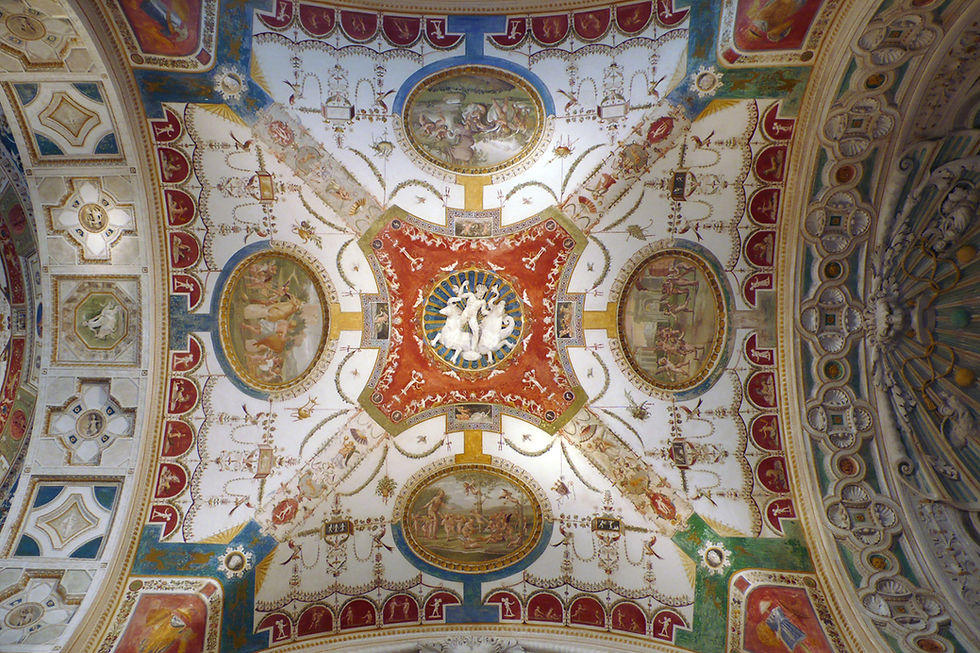

Not only did I reconstruct the absent architectural form—from the proportions of the exterior order to the shape of the roof—I also imagined what it would be like if it were frescoed and stuccoed (à la Raphael’s Loggia; see below). For which essentially no evidence exists. And eschewing copying—partly since no model would fit precisely, and partly to invest the reconstruction with an appropriate iconographic program—meant imagining, effectively designing, the decorative treatment of walls and ceilings.

The peer review process challenged me to justify all the choices I made, and to prove my familiarity with the scholarly literature on the topic; much credit to the editor, Margaret Laird, for her patience and precision. The scholarly trade is extremely rigorous in ways that few people who don’t read serious architectural history can appreciate or even recognize. The only thing that I, as an artist-architect, could really contribute is the ability to imagine, and graphically document, that which does not exist in the archives, something scholars are mostly loath to do. I’m convinced that has scholarly value because a credible understanding of intention demands some idea, some image, of the result of the intention. And when the result doesn’t exist, or exists only fragmentarily, architects and artists can provide a version of it.

Which is, I hope, an argument for more collaboration between scholars and creative disciplines, as happens in music, or in historically informed opera performance (costumes, sets, gestures). And, I would guess, even in culinary history. If the Nymphaeum was also meant as a dining loggia, I wonder what would have been eaten there?

Buon appetito!

Not sure I can imagine what was eaten there, although I suspect that whatever it was, it was probably healthier than the junk we eat today! But I think a drawing/investigation like this is very important for the following reason: archaeology used to be part science and part art, and the art was often the architects and artists speculating about what something might have been (like here), even with the most fragmentary evidence. What was often produced in those speculations was incredibly useful and artful, and even if not archaeologically correct, advanced the discussion on the "art of the possible." Today, archaeology seems to be much more focused on the science of archaeology, a positivistic approach that diminshes speculation …